This history is not symbolic. It is specific, embodied, and carried forward through language.For many Black American women, forced renaming has ne

This history is not symbolic. It is specific, embodied, and carried forward through language.

For many Black American women, forced renaming has never been a side detail of oppression. It has been one of its primary tools.

During chattel slavery, Black women were stripped of their given names and renamed for ownership, convenience, and surveillance. Names tied to lineage, geography, spirituality, and kinship were replaced with labels that made Black women legible to systems, not recognizable as human beings.

As the famous trial of that time shows, State of Missouri vs. Celia, a Slave, enslavers renamed Black women to mark them as “property” , to disconnect them from ancestry, and to reduce them to what could be extracted from their bodies: labor, unlimited access to their bodies through rape from childhood years, reproduction, and obedience.

A Black woman’s identity was not hers to define. It was assigned.

That pattern did not end with emancipation. You hoped that it did but it didn’t.

In the post-slavery era, Black women were renamed again through policy and pseudoscience.

They became “breeders,” “domestics,” “dependents,” “wards,” “unfit mothers.” Medical and academic institutions classified Black women by reproductive capacity rather than personhood. Gynecological experimentation and forced sterilization was performed on enslaved and poor Black women whose pain was dismissed as irrelevant, whose bodies were studied without consent, whose names were often omitted entirely from records. What mattered was anatomy. Function. Utility.

During Jim Crow and the rise of social welfare systems, Black women were renamed once more. Terms like “welfare mother,” “illegitimate,” and later the mythologized “welfare queen” reduced Black women to caricatures defined by reproduction, dependency, or moral suspicion. Again, naming was not descriptive. It was disciplinary. These labels justified surveillance, punishment, and public contempt while obscuring the structural violence Black women were navigating.

Each renaming served the same purpose.

To distance Black women from full humanity while claiming bureaucratic neutrality. No renaming benefitted Black woman. That was never the intent.

So when modern political or institutional language begins describing Black women primarily through biological processes, organs, or functions, many Black women do not hear innovation. They hear continuity.

They hear the old move dressed in new syntax.

This is why the objection is not simply about terminology. It is about historical memory. For Black women, being referred to in the third person by biological shorthand echoes a lineage of control that has always preceded harm. When a woman is no longer addressed as a woman, it becomes easier to debate her safety, override her consent, or minimize her pain.

Some argue that this language is “inclusive”” or “technically accurate.” What could be the problem? Everybody in this conversation knows what the “problem” is.

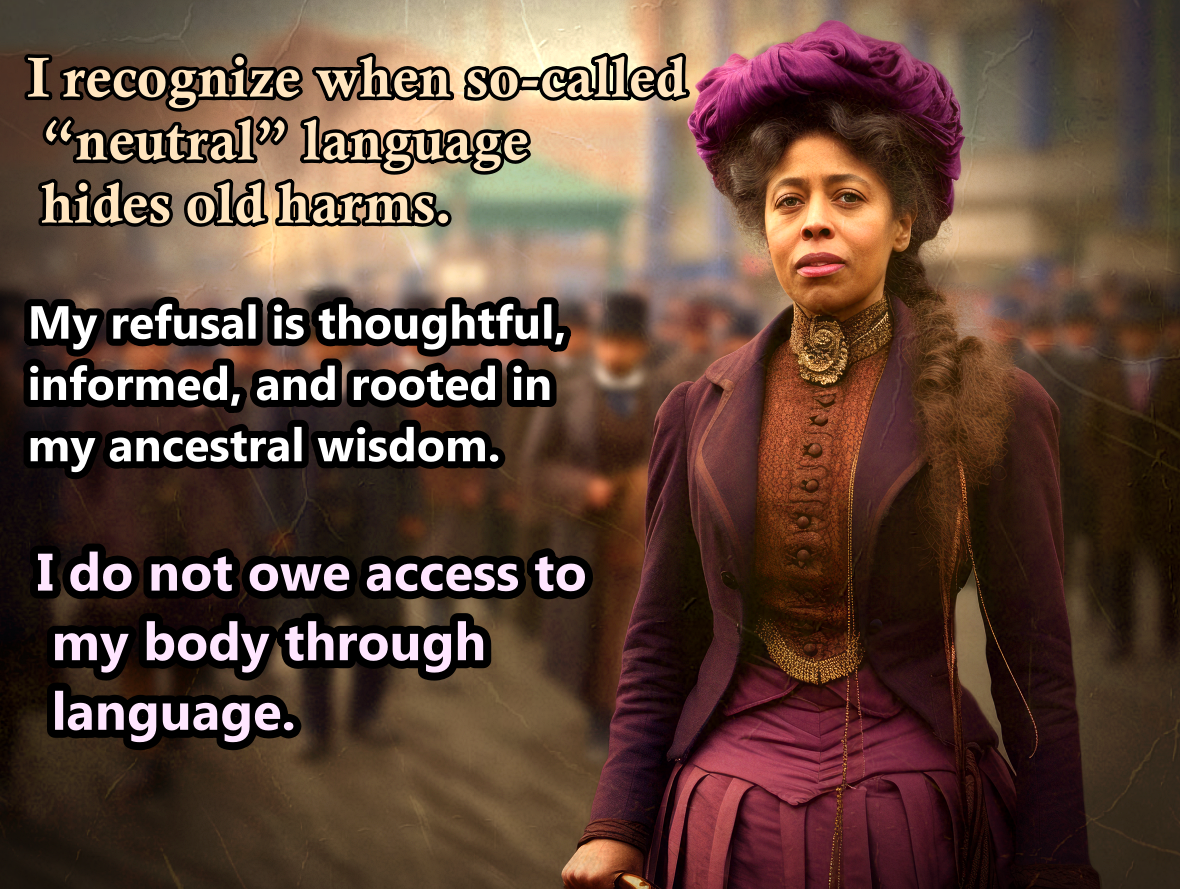

And Black women know that throughout history, “neutral” language has often been the most dangerous kind. Neutrality has repeatedly been used to mask domination, to flatten lived experience, and to sidestep accountability.

Consent has almost never been part of this process. And forget about helping, uplifting or serving Black women.

Black women were not asked before they were renamed in slavery.

They were not asked during medical exploitation.

They were not asked when policy labels followed them into every institution.

So when Black women now say “no”, they are not resisting progress. They are exercising agency that was long denied.

This is also why political institutions, often misread the moment. What is interpreted as messaging discomfort is, for Black women, a boundary rooted in survival. Black women have supported movements, parties, and reforms while still refusing language that erases them. Those two truths can coexist.

Many Black women are saying something precise:

We will not be renamed without consent.

We will not be reduced to parts when we have always been whole.

We will not accept dehumanization simply because it arrives wrapped in progressive intent.

That is a dead end road for Black women and everybody knows it.

Some Black women choose different language for themselves. That choice deserves respect. But so does refusal.

History teaches Black women that naming is power. Whoever controls the language often controls the outcome.

This is why Black women are attentive now. Not reactive. Not confused. Attentive.

They are listening for whether the future being offered honors their full humanity or simply retools an old habit of extraction with better branding.